Article by

Sam Millunchick

Posted on

October 24, 2025

Article by

Sam Millunchick

Posted on

October 24, 2025

A masterclass in conviction under pressure: why founders don’t lose deals for lack of a good pitch, but because their nervous system betrays their doubt—and how to retrain it into composure that sells.

Alex Hormozi likes to talk about this parable when he's discussing price:

If you had a ferarri that you offered to sell to someone for $5k, and they knew it was a legitimate deal, they would do everything in their power to get that $5k.

And he's right, of course, no matter what you think of him. Value is value. It speaks for itself.

But think about your position as the seller—you also would have unshakeable conviction that you were offering something of worth. There would be no shakiness, no doubting, no "I wonder if this is a good deal for them," or "will it work out". You'd know that someone would buy this—it's too valuable not to.

That's what it means to operate from conviction. And it's exactly what people don't have when they're starting or scaling up a business. Yes, of course they believe in their product; if they didn't, they wouldn't be doing it in the first place; but there's something more pernicious at work with founders and pitches. There's an identity transference, where the founder becomes synonymous with their work (only in their own heads, but alas, that's the biggest problem).

Once that identity transference takes place, it goes both ways—the founder is the product, but the product is also the founder. And if that's true, then all the insecurities, foibles, and doubts of the founder are in the product as well. It's no longer just selling or pitching, or really, if we're where we should be, offering. Instead it's "please pick me, to show me that I'm worth something" and it's "I'm nervous I'm not good enough (and therefore I'm nervous the product is not good enough)."

And boy oh boy does this come through when you're speaking. It looks like hedging, or apologising, or limiting. It looks like trailing off at the end of a sentence or a weak tone. What it doesn't look like is offering you a ferarri for $5k.

Paradoxically, then, what founders need to get signed is not better messaging (most of the time; there are exceptions)—it's a better relationship with themselves and other people. When you sit across from me on a zoom and say "I can't understand why we're not funded yet" with 200k ARR, the answer is staring you in the face. It's you. People have been funded on a deck and a dream, and you have a quarter million in ARR? What do you think the problem is?

All this is based on the idea that we pick up on signal much more than we pick up on words. And that signal is transmitted on so many different wavelengths that we're not even aware of—like infrared light, we're blind to it but it's damn well still there.

So what we need to fix is the nervous system, the relationship to self, and the way that gets expressed in the world.

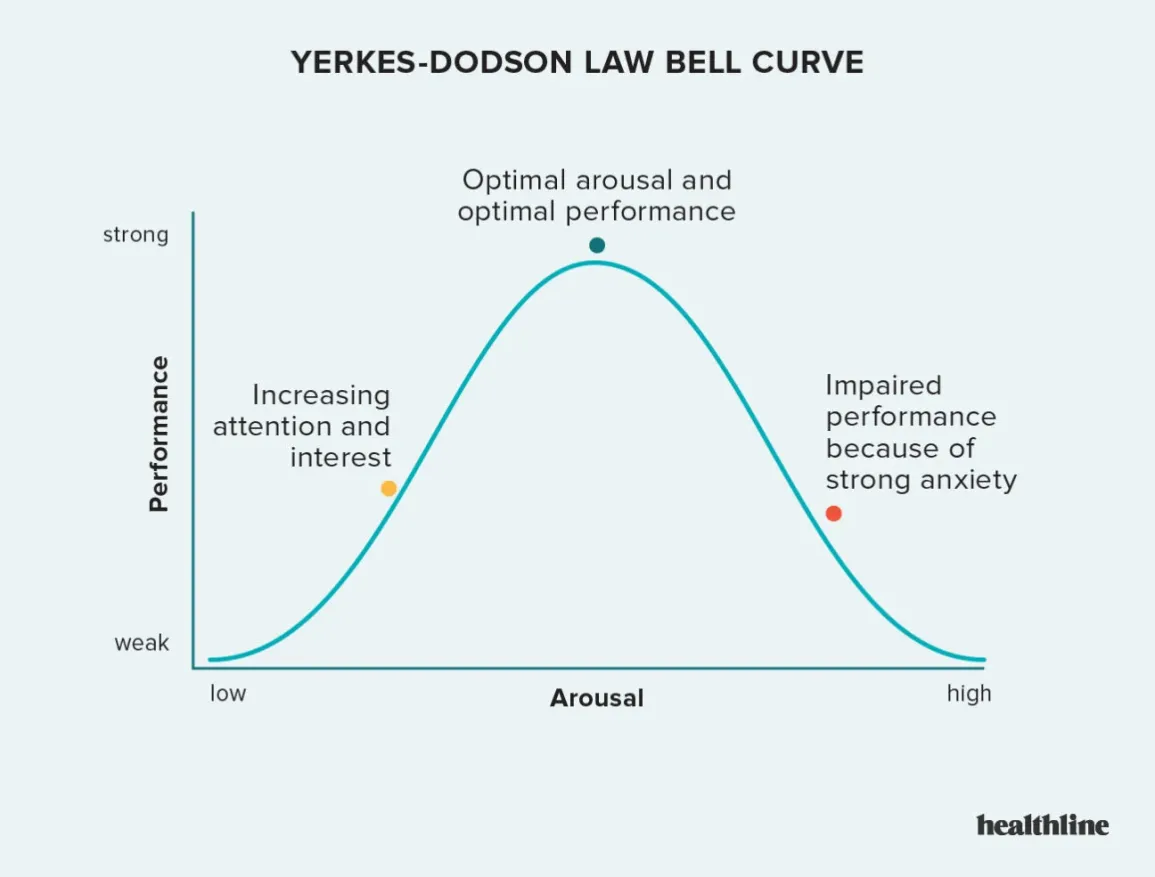

If your body's pumping more adrenaline than a soldier in a gunfight, you're going to underperform, or potentially even choke (not like physiological choking. I mean mental choking). This is because of something called the Yerkes-Dodson law (YDL):

The YDL states that if you're either under or over aroused, you won't perform well. You need to be in that middle, sweet spot of somewhat nervous (no one who cares about an outcome is not nervous at all!) but also calm enough not to lose it on stage (or during the pitch).

The mechanism behind the left-hand side of the curve is fairly obvious—if you're disinterested, you're ngmi because you simply won't put in the work. The mechanism for the right-hand side is more pernicious though. You have a part of your brain, one of the oldest parts, called the amygdala. One of the functions of this primitive part of the brain is to regulate fear. Normally the amygdala is regulated itself by the pre-frontal cortex, the newest part of the brain that sits at the front, by the forehead, and controls the higher, so-called "executive functions" of humanity (like self-control, for example).

But that amygdala is there for a reason. Fear is adaptive—you definitely want to be afraid of dangerous things so you live longer—and therefore it has a free pass to take over the PFC when it senses existential danger. Your "thinking" brain literally shuts off as the more primitive parts figure out how to survive. Adrenaline and cortisol flood your system and your body gets ready to react.

All this means that the more scared you are, the closer you inch towards the left-hand side of YDL curve, the more your thinking is off and your reactions are on.

This fear leaks through everything, no matter how you try to keep a lid on it. Our bodies are amazingly interconnected systems. We're also built to live in tribes, and so are exquisitely sensitive to other's behaviour as well. This is also adaptive—if we don't directly sense danger, but can sense it through the signals and behaviours of someone else, then we stay alive and get to see another day.

So in a co-evolution, we've adapted to both give off signals of fear, as well as receive them. It pervades our voice (tone, timbre, rhythm), our movements (jerky, shaky), and our actions (more blunt, less fine, precise, thought out). When we see this, we see fear. We recognise it as fear.

We wouldn't be afraid selling our Ferrari, but we are selling our startup idea or our ideas at work. This fear is a signal, "my product isn't good enough." That's why your calls close with "we'll think about it" or "we need to see more traction" when you're already at $200k ARR (real story, btw) whilst others are at $0 ARR and are crushing it with investors.

It's never about the pitch. It's always about the founder. The idea is table stakes—no one's taking a meeting if the idea's bad. What gets it over the line is conviction.

Real presentations have all sorts of rough edges. Hostile questions, time pressure, tech failures, unexpected skepticism. All of these have to planned for, practiced for, and finally, let go of before the big day.

What we want is practice that allows us to stand tall on a rocking boat in choppy seas, not just in tranquil waters. That's the difference between confidence and composure. Confidence says, "I've done this before so I can do it again," and when it's not exactly like before, it cracks. Composure says, "no matter what happens, I'm ready. I can adapt. I have trust in my ability to find my calm and deliver the best performance I can, no matter the circumstances."

So if the problem is your nervous system broadcasting fear, how do you fix it? Not by trying harder or bullying yourself into calmness, but by training your autonomic system the same way an athlete trains their body—systematically, under progressively increasing load.

The first thing to fix is the most obvious: the visible tells: shaking hands, voice going tight (and high), speaking too fast, breaking eye contact when challenged (or going blank). These are autonomic nervous system responses, and even though it's not under conscious control by default, but it can be trained.

The best lever I know of for that is breathwork.

Not meditation or "take a deep breath and relax" type of stuff. I mean tactical breathing protocols that shift you from sympathetic dominance (fight-or-flight) to parasympathetic activation (rest-and-digest). The mechanism is straightforward: when you extend your exhale beyond your inhale, you stimulate the vagus nerve, which acts as a brake on your stress response.

We start simple and build a daily breathwork routine to train the nervous system's baseline so that when pressure ramps up, there's more range in your system before tipping into the overload zone on the YDL curve.

Then there's the pre-event protocol: 90 seconds before walking into any high-stakes situation, do what's called a physiological sigh. Two quick inhales through the nose (the second one tops off the lungs), then a complete exhale through the mouth for three rounds. It sounds absurdly simple, but it works because it rapidly offloads CO₂ and resets arousal level.

We make this a ritual, and the best part about it is - breathwork goes where you go. It's low tech, always-on, and works as long as you're alive.

What ends up happening is that you stop the visible tremors of the autonomic nervous system, not because you feel calm—you're still nervous, and that's fine. But because we've shifted you from the right-hand side of the YDL curve (too much arousal, PFC shutting down) into the sweet spot.

For those whose tell is speed—talking faster under pressure, which makes them less clear, which makes them more anxious, which makes them talk even faster—the work is different. We train pauses, deliberate, controlled silences. When the urge to rush hits, we take that as our cue to stop and take one full breath. That breath gives the PFC a second to catch up with the mouth.

Now, I will tell you that two seconds of silence feels like an eternity when you're being watched, but to an observer it just looks like composure (and will also feel half as long). You're transmitting as someone who's thinking before they speak. And crucially, it breaks the doom loop.

This is what signal stability looks like: not the absence of nerves, but control over how those nerves express themselves. Your investors can't see your heart rate, but they can see your hands, hear your voice, watch your eyes.

But controlling your body is only half the battle. Your thinking still has to work when someone attacks your assumptions.

This is where most people fail. They walk in prepared for the pitch they practised, and then someone asks a question they didn't anticipate, or challenges their gtm strategy or timeline, or says "I don't believe that number," and suddenly their brain goes blank, or worse, it goes into defence mode—rambling, justifying, explaining too much.

We know that this is happening because the amygdala has hijacked the PFC. So we don't try to think better under pressure. We train to think differently—using frameworks that scaffold us even when our rational brain collapses.

Like the rule of three: any answer has three parts, maximum.

Pyramid principle: answer first, then support.

SCQA: Situation, Complication, Question, Answer.

When your brain is under load, the framework holds the structure so you can focus on content.

Some other changes we make are around mindset and the way we look at and talk to ourselves:

This is cognitive endurance: not thinking harder, but having systems that hold you up when thinking gets hard.

And here's where most training fails completely: people practice in comfort and expect it to work under fire. It doesn't.

The answer isn't more practice, it's different practice, practice that matches the stress profile of the real thing. This is called pressure inoculation, and it's borrowed from military training and exposure therapy.

So we don't practice the pitch. We practice recovering when the pitch gets derailed. And we don't just practice handling these disruptions, we practice the recovery. When you lose your train of thought, how do you get it back? When someone derails you with a tangent, how do you redirect? When you feel the adrenaline spike, what's your reset protocol?

This is the difference between confidence and composure, the distinction I made earlier. Confidence says, "I've done this before exactly like this, so I can do it again." Composure says, "No matter what happens, I have tools to find my centre and deliver." Confidence is brittle. Composure is anti-fragile.

As we used to say in the army - "tough in training, easy in battle."

Train all three (signal stability, cognitive endurance, and pressure inoculation) simultaneously, under stress that progressively ramps up, and what you get is what people call "executive presence" but can't teach you how to build. Because they're teaching content and delivery. We're engineering nervous system resilience.

That's what composure actually is. Not the absence of fear but control over how fear expresses itself, not feeling calm but staying coherent when calm isn't available.

If you're brilliant in private but crack under scrutiny, your problem isn't your story. It's your signal.

And signal can be engineered.

Book a free 30-minute strategy session with me.

I guarantee it’ll be the most productive half-hour you've had in years. We’ll dig into your specific challenges and you’ll leave with actionable tips you can use right away.

In the startup world, the best communicator often wins. Make sure that's you.